Not everyone wants to staircase to 100%. Perhaps you bought your Shared Ownership property as a ‘starter home’, hoping to make a gain on your share so you could buy on the open market. Or perhaps you rely on Universal Credit to pay your housing costs and you chose Shared Ownership as a more secure form of renting than the private sector.

However, staircasing features prominently in Shared Ownership advertisements, so it seems likely that it is an aspiration for a great many shared owners.

That being said, staircasing is not right for everyone, and some shared owners may find it more challenging than they expected to staircase to 100%. Let’s take a look at four reasons this might be the case:

- Property prices

- Wage inflation

- Rent increases

- Unexpected life events

We’ll take a look at the statistics on how many shared owners succeed in staircasing to 100%. And we’ll also explain some things to think about if you don’t, or can’t, staircase to 100%.

Common reasons why people don’t staircase to 100%

1. Property prices

When the Government first introduced Shared Ownership in the late 1970s, the intention was for people to buy an initial share then purchase the rest of their home at a later date – when they could afford it. For this reason, Shared Ownership is sometimes described as a scheme where you pay in instalments. But this is not really an accurate description. For example, say you bought a car using an instalment payment plan. You would have to make monthly payments until you had paid off the total sales price of the car (plus interest on your loan for the car). However, the price of the car itself wouldn’t change from the sales price agreed at the commencement of the payment plan.

But it’s different with Shared Ownership. Each time you staircase, the amount you have to pay is calculated based on the ‘current market value’ of your property. And it is impossible to predict the cost of your next share at the time you buy your initial share; no one knows for sure how property prices will perform in the future.

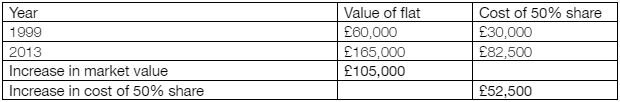

Anna - Example 1

We’ll use a one-bedroom flat in east London as an example. The shared owner – let’s call her Anna - bought an initial 50% share in 1999, when the flat was valued at £60,000. So the first 50% share cost £30,000. In September 2013, Anna staircased to 100%. By then the flat was valued at £165,000, so the second 50% share cost £82,500.

This is more than her entire property would have cost in 1999.

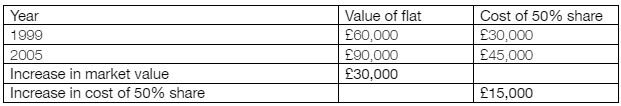

Anna - Example 2

This time, let’s imagine Anna staircased in 2005, six years after she bought her first share. A similar one-bedroom flat in the same block sold for £90,000 so we can safely assume the market value of her flat would have been around the same. This time the increase in cost of Anna’s second 50% share (compared to the initial 50% share) is ‘only’ £15,000.

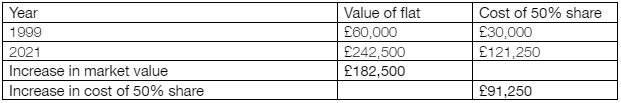

Anna - Example 3

Now let’s bring things as up-to-date as we can. Another one-bedroom flat in the same block sold for £242,500 in 2021. Imagine that Anna didn’t staircase in 2013 or 2005, but in 2021. This time she would have to find £121,250 to staircase to 100%. Her second 50% share would cost £91,250 more than she paid for her first 50% share back in 1999.

In fact, the price increase of her second 50% share would be £31,250 more than the entire flat was worth back in 1999 when she bought her initial 50% share.

The two different pathways to full home ownership

We already mentioned that some people buy a Shared Ownership property as a starter home, hoping to make a gain on sale. Rising property markets will be good news for those taking this pathway to full home ownership. But anyone hoping to staircase their way to full home ownership may find they get priced out if property prices rise faster than their income.

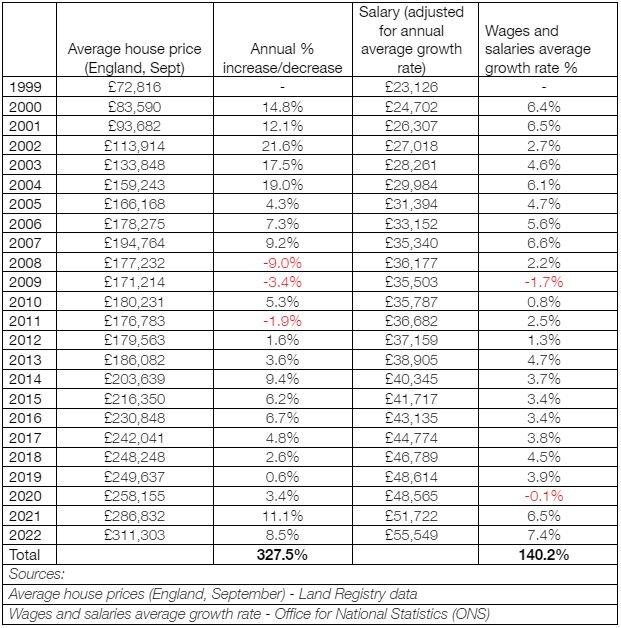

2. Wage inflation

Do property prices rise faster than average household incomes? It’s a complicated question to answer. Property markets vary around the country. And average household incomes can also vary according to where you live, or whether you are a one-adult household or a two-adult household. Nonetheless, it is still helpful to look at national average annual wage increases/decreases to see if household income tends to keep pace with property market movements.

What this illustration demonstrates is that, historically, over the last 20 years, property prices have risen a lot faster than typical household incomes. If you had waited too long to staircase to 100%, you would have run the risk that buying more shares would have become increasingly unaffordable.

3. Rent increases

Shared Ownership rent is often described as ‘subsidised’. However, rent increases annually at a rate pegged slightly above inflation (usually the Retail Price Index (RPI) plus 0.5% or RPI plus 2%). Additionally, annual rent reviews are carried out on an ‘upwards only’ basis so your rent will never go down, even if inflation does. In fact, although Shared Ownership rent starts off subsidised, it can sometimes end up higher than private rents on comparable homes in your area.

Another factor to take into account is that the smaller your share, the more exposed you are to ongoing rent increases. For example, if you have a 25% share you will pay more rent than someone who bought a 50% share in a similar property at the same time, and your rent increases will mount up faster.

Let’s take a look at how annual rent increases play out for our shared owner, Anna.

Anna - Example 4

Anna bought her initial 50% share in 1999, so she has an older lease. The terms are different to more recent leases. In Anna’s case her initial rent was calculated as 4% of the value of the property held by the landlord. Her lease also specifies an annual rent increase of RPI + 2% or 5%, whichever is higher. Her annual rent review uses the RPI rate published the previous November.

You may find that your own lease specifies initial rent as 2.75% of the landlord’s share (or a different amount). Recent leases often require an annual rent increase of RPI plus 0.5% or 0.5% whichever is higher. But this could be higher on resales of older leases. You will need to check your own lease terms to see exactly how your initial rent and subsequent annual increases are calculated.

Anna – Example 5

In the next example, we assume that Anna had the same terms as a more recent lease – i.e. that her initial rent was calculated as 2.75% of her landlord’s share, and her annual rent review increase was the higher of RPI + 0.5%, or 0.5%.

Of course, the larger your share, the less exposed you are to rent increases but the more exposed you are to mortgage rate fluctuations. However, your mortgage will eventually be paid off, while you will carry on paying rent forever (unless you staircase to 100% or sell your home).

To keep things relatively simple, we’ve ignored service charges, estate charges and ground rent in these illustrations. We’ll discuss these costs briefly later in this article.

4. Life events

Whether or not you staircase to 100% will depend, in part, on your personal circumstances. Maybe you will get a pay rise at work or change career. Perhaps you buy your initial share as a single person then meet a significant other who can share housing costs with you. Or you could benefit from a windfall such as an inheritance. Any of these events could help you staircase. But, clearly, it is not sensible to base future staircasing plans on life events that may or may not happen.

On a less positive note, you might run into financial difficulties you didn’t anticipate - such as redundancy or health issues – which could undermine your plans to staircase.

How many people staircase to 100%?

Oddly, nobody really knows exactly how many shared owners have successfully staircased to 100%. But a 2021 Parliamentary briefing report says: ‘The number of people staircasing to owning 100% of the equity in a property is fairly low’.

And the Law Commission say: ‘The vast majority of shared ownership leaseholders will never staircase to 100%’.

Why doesn’t anyone know how many shared owners have staircased to 100%? The main problem is that no one collects this data. You may have read that, generally speaking, around 2-3% of shared owners staircase to 100% each year. However, these national statistics include two very different types of staircasing:

- Shared owners who achieve full home ownership by staircasing to 100% in a home they continue living in

- Shared owners who are obliged to staircase to 100% as part of a simultaneous sale and staircasing transaction, purely in order to sell (but who only make a gain – or loss - on their part share)

This suggests that the number of shared owners achieving full home ownership via staircasing is even lower than 2-3% (for all the reasons we’ve discussed above). How low? No one knows!

So what happens if you never staircase to 100%? (And are there any downsides if you do!)

Rent

As we pointed out earlier, a mortgage will eventually be paid off but you will carry on paying rent to your landlord forever - assuming you don’t staircase to 100% and that you don’t sell your home.

Your rent may be affordable at the moment. But it’s worth thinking about what would happen if your household income decreased - say, in retirement or due to redundancy or ill-health – and you were struggling to pay rent (or other housing costs such as service charges, ground rent and estate charges, if applicable).

Assured tenancy

From a legal perspective, Shared Ownership is an assured tenancy until you staircase to 100%. One of the main hazards of an assured tenancy is that you could be repossessed if you fall behind with your rent. And, if you are repossessed, as a ‘tenant’ you could potentially lose all the equity you have invested in your home.

Another downside of assured tenancy is that you have no statutory right to lease extension.

Lease extension

Anyone buying a Shared Ownership home under the Government’s new model will benefit from a 990-year lease. But many thousands of households have already bought short 99- or 125-year leases. And the bad news is that these leases will continue going down in value year after year (all things being equal) once there are fewer than 80 years remaining on the lease. This could make it harder to re-mortgage or to sell.

Even if you never staircase, you may still need to pay to extend your lease if you do not want the value of your share to go down. Although you do not have a statutory right to lease extension, your landlord may allow you to extend your lease via what is known as the ‘informal route’. However, this offers fewer rights and protections than the statutory (or ‘formal’) route to lease extension.

Some Housing Associations charge the premium for lease extension based on your percentage share. But others charge it on the full value of the property making lease extension poorer value for money if you have only a small share.

Ground rent

A ‘ground rent’ is a payment paid by residential leaseholders to their landlord. The landlord does not have to provide a clear service in return.

Historically Shared Ownership properties were offered with ‘peppercorn’ ground rent (effectively zero). However, a number of Shared Ownership leases now include ground rent.

One way for leaseholders to eliminate a ground rent is to undertake a statutory lease extension, as this automatically reduces ground rent to a ‘peppercorn’. However, as we pointed out above, shared owners do not have a statutory right to lease extension so may have no way of dealing with high ground rent charges.

Subletting

Shared owners are not allowed to sublet except in ‘exceptional circumstances’. Even then, you are not permitted to make a gain on subletting and there may be other restrictions such as a fixed time limit. However, usually you are allowed to sublet once you have staircased to 100%.

You may have no intention of subletting at the moment. But not having the option to sublet might lead to financial challenges in the future, say, if you needed to temporarily relocate for work or for personal reasons (say, your children’s education or family caring responsibilities).

Selling

Depending on the size of your share, you may find it harder to sell your home than if you had staircased to 100%. For example, if you have an 80% share you may find that anyone who can afford such a large share might actually prefer to purchase a home on the open market. Or, depending on the current market value of your home, it is possible that anyone who had a high enough income to obtain a mortgage for your share might earn too much to meet eligibility criteria surrounding maximum household income.

What happens when I die?

Rent on the share owned by the landlord will still be payable after you die (along with service charges, estate charges and ground rent if applicable).

As a lawyer explains: “The monetary obligations on a shared owner when they’re alive are significant. The thing to remember is those obligations don’t cease when that person passes away. Instead, it will fall with their estate”.

Although rent and other costs should be paid out of your estate, they may mount up, especially if it proves time-consuming to sell your property. This could reduce the value of the inheritance to your beneficiaries, perhaps substantially.

Downsides of staircasing to 100%

You might think there are no downsides to 100% staircasing. But there is one pitfall to be aware of. Even if you do not pay ground rent at the moment, you might have to pay it once you have staircased to 100%. Ground rent can be fixed or escalating. If ground rent is fixed it will stay the same. If ground rent is escalating then the method for calculating increases will be specified in the lease.

The Government has introduced reforms ending ground rents on new leases. But this reform is not retrospective, so will not benefit anyone who is currently exposed to ground rent on staircasing to 100%.

Do your own research!

Different Housing Associations have different policies on everything from staircasing to ground rent. Make sure to check with your own housing association, and your solicitor, if you have any questions.